Family outcomes - what happened to everyone?

I have a Masters degree in epidemiology - the study of health and diseases over populations. So as I gathered more descendants of George and Jean Buchan, well I thought 'why not keep going?' Find out what happened to all of them, as individuals, as family units and as people in society.

This started out looking at mortality and then emigration. So far I am still trawling online sites, and contacting cousins in the hope of completing the 'study population' - we Buchans! With all but the line of George b1802 completed, I will soon be able to get started on the descriptions and statistics.

The following text is an article in my local family history society journal.

Whole family outcomes: uncovering what happened to

everyone

I have wondered how my direct biological family line fits

within broader human experiences of their region and their country. How ‘representative’

of the general population is my family, or yours? In family history, when we

focus on just our direct biological line, or that part of our family that

settled in one small place, that is all we can see. Conversely, the human

population is so large, that even our tiny pool is still a lot of people. Where

to draw a boundary of who is my family? This article describes the start of a

“whole family outcomes” study where I hope to provide a highly granular answer

to how my family lived in Scotland from 1799 to the present day: its size,

family patterns, religion, employment, death and movements around both Scotland

and the wider world. At times I could compare this to county and country

statistics.

One-name studies are based on searching indexes and

exploring documented individuals to bring life to this heft of ‘families’. Like

family history, they often self-select those who went on to ‘have families’,

ignoring the single people and those who died in childhood. I know the impact

of child-hood loss, I recognise the impact of ‘great-aunts’ and other

undocumented people. I want to see my entire family in as much detail as

possible – which requires the information found on BMD certificates. Such a study is made possible because of the

availability of online records and ScotlandsPeople in-person access, as well as

the great flourishing of interest in family history that has spawned

mega-genealogy databases, archive digitisation projects and on-line trees [at

least those that are well documented!]

Perhaps I am intrigued by population studies as I lack an

inheritance of primary records such as diaries, letters or significant community

involvement. Much science and knowledge has been born from collating enough of

the whole to avoid erroneous conclusions. Why not family history too?

My target study population

I trace my working-class Buchan family back to 1799, when a

baby boy was born to George Buchan and his wife Jean Johnson, perhaps in the

tiny village of Dewarton in the county of Midlothian. I say ‘perhaps’ because

he was baptised along with two brothers some years later. They truly could have

come from anywhere, but my guess is from the neighbouring parish. All told

these parents had nine children from 1799 to 1818, the last being born in the

week her father died. From this humble beginning has grown a family exceeding 3,000

people and clearly there are ones I don’t know about. The majority, perhaps

75%, stayed in Scotland, and because of this I can trace their families to the

present day.

There are three main sources of capturing these Buchan

descendants.

1) * Through indexes on ScotlandsPeople (SP), the

outward face of the National Records of Scotland. These begin in the 1550s,

although are sparse in early times. Till 1855 these records were made by parish

ministers, some more diligently than others. From 1 January 1855, civil

registration was compulsory in Scotland; by about 1870 it was almost universal,

say the experts. The FreeBMD site provides a [not complete] similar index till

the year 2000. A surprising number of USA vital records are also open public

documents, according to state regulations.

2) * Through family contacts, here in Australia and

through on-line trees. Due to SP above, I can verify many of these trees, so

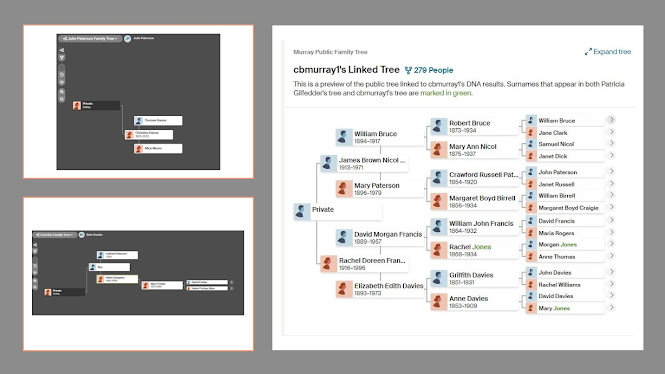

that the accuracy of family reconstruction is much improved. DNA matches I

collaborate with have provided family details.

3) * Through DNA evidence. One thing can be said of

almost all the 1,500 people who match me or my siblings and other tested family

members; we are biologically related at the 4th cousin level or

closer. Using techniques that ‘corral’ matches into my family lines, I can be

sure that a particular match is on my Buchan line. Although these living

relatives are often not visible on family trees due to privacy provisions,

their accompanying trees provide details of their deceased grandparents, and

these can be linked back to existing family branches and verified again through

SP. DNA is also providing evidence of unexpected and undocumented family

members, usually through illegitimacy or ‘cohabitation’. No longer the stigma

it once was, these children all belong to my big Buchan family. This has been

very helpful for Buchans not born in Scotland.

Neither George or Jean has a baptismal record, a marriage

record or a death record before 1855. Without such records I do not know who

their parents and siblings were. In contrast to rigid recording of families

since 1855, prior to this time, in Scotland marriages did not need a priest to

be legal; multiple splinter religious sects kept and destroyed their own

records, if they kept any at all, and very few burial records were made. My

original plan was to use DNA to find this couple’s parents, but autosomal DNA

has reached a limit for me. George and Jean are my x4 great-grandparents, and

the accepted limit is x3 great-grandparents where I and my matches can reliably

expect to still have these ancestor’s DNA in our own cells. [Footnote – an

extraordinary exception is my brother and our half 4C Helen who share an off

the chart 98cM, being DNA exclusively from one of the siblings, Robert Buchan,

which is of course entirely the DNA of George and Jean!]

Consequently, I started a study with my father’s cousin’s

DNA, my 1C1R[older], since George and Jean were her x3 great-grandparents. In

building a DNA network of over 200 descendants of this couple, I found 15 other

people in the same generation across the entire world. So far eight of these

people have shared their DNA, and I hope to convince several more to do so. I

have a Canadian, some Scots, English and Australian folk in this select group

who have more of George and Jean’s DNA than most of us do. But the goal of

finding their parents is so far eluding me. In the meantime, I have turned 180

degrees to focus on their descendants.

Completeness of data

The keystone of a population study is an accurate population.

Eight of the nine Buchan siblings died after 1855, while the other was an

unnamed infant who died in 1808. Six of these adult children married and had

families, and all eight survived till at least 65 years. In classic oldest and

youngest child obligations, neither of these two siblings married. The oldest

son, aged 19 when his father died, took on his father’s occupation and provided

for his mother and siblings throughout his long life; while the youngest, a

daughter, looked after her mother and then her nieces and nephews till she was

the last of the siblings to die. This brother and sister lived together all

their lives in the same house and were ultimately buried in the same plot.

The six fecund siblings were William b1801, George b1802,

Isabella b1805, Andrew b1809, Robert b1813 and Alexander b1816. Their family

sizes varied from three to ten children. All told George and Jean had 37

grandchildren. Below is a graph of the descendants of the six siblings as I

knew it in April 2025. This number has doubled since going to Scotland in May

2025.

The key condition making such a study feasible is the

ability to purchase Scottish birth/baptism, marriage and burial/death records,

and download them instantly, for about $2.50 each. A similar record costs at

least $20-40 in Australia. There are restrictions, as in Australia, along the

lines of 100 years for a birth, 75 years for a marriage and 50 years for a

death, for being able to purchase an on-line certificate. However, SP provides

an opportunity to view these restricted certificates in their six ScotlandsPeople

Centres. You can not capture an image, only transcribe the information. You pay

£15 a day to view as many of these certificates as you can. I spent eight days

in two centres, Edinburgh and Hawick. I transcribed over 1,000 records; but I

viewed very many more.

A problem with consulting indexes is common names. Scotland

is like many countries where first names are re-used acknowledging close

relatives. For boys – James, Robert, David, William, John, Alexander, George –

all used in the Buchans. For girls – Margaret, Helen/Ellen, Ann, Isabel[la],

Mary, Jean/Jane/Jessie. How I longed for a Grizel, or a Horatio. Instead, I had too many James Jamiesons and

John Browns. Such names are impossible to sift through on death records,

especially when maternal surnames were not included on the index for many years.

A birth will be indexed under both parental names, with a time frame and a

location – facts generally known for our families. A death can take place

anywhere!

I love Scottish naming patterns. In the 18-19th

century these were commonly followed, similarly to the Irish. Additionally,

Scots liked to name their children using the ancestor’s entire name. Not just

Annie for her grannie. The wee child was named Annie Dougall Mackenzie Buchan because

her grandmother might have been Annie Dougall Mackenzie. It is common for all

Scottish children to have one or more surnames as middle names; many surnames

are now ‘common’ first names for boys – Donald, Craig, Gordon, Grant. Similarly,

many boy names have become surnames such as Jamieson, Dickson, Johnson. Finally,

many girls’ names have been ‘girlified’ – Thomasina, Donaldina, Davidita.

Going into the SP Centres allowed me to check the entire

page of James Jamiesons in any time frame – sometimes all 20+ of them. Over 90%

of the time I found the one I wanted. Sometimes during war times there might be

five or more people of the same name and age killed in the war, and no detailed

death certificate exists. War memorial lists helped some of the time. There

were people who could not be found in Scotland; they had emigrated. Some of the

time I could find them, but there is a group whose size is not known to me.

When I returned to Australia with relatives correctly

identified, with new information such as names of spouses, I was

able to build out more family units to the current time.

Information I now hold

For family reconstruction, I need two parents, but one might

have to do, a birth date and place, a marriage date and place, and a death

date, place, cause and informant. Scotland also gives me time of birth and

death, and the usual residence if the death occurred in a hospital or on a

ferry. It gives the address and relationship of the informant on almost all

deaths and some births, and some witnesses to marriages as well. Occupations

are recorded on all certificates, for fathers and informants [mostly], but in

the 20th century increasingly for woman getting married, and on

their death. All SP records are indexed under both the maiden and married

surnames of women!

These outlines of family life can then be filled in by

census data, changing occupations, changing locations, sometimes newspaper,

court records or family-held information.

Collating the data

My family history software cannot analyse occupation,

migration and mortality data. So, I created an Excel spreadsheet that will

later go into an Access database. At present I keep the descendants of each

sibling on a separate worksheet, but these will be combined in Access.

To keep individuals straight in my head, when so few first

names are used in each generation, I created an indexing system that also gives

clues to family position, which I place in the suffix field of their name. Each

of the original siblings was termed 1, 2 through to 6. My ancestor Robert

Buchan is number 5. Hence all his descendants’ numbers start with 5. His nine children

are thus 5.1, 5.2 … 5.9. I name these chronologically, regardless of how many

spouses the parent had. Robert with one known wife, one known liaison, and one

‘just unknown relationship’ [although I have her name] is seen as the father of

all nine regardless by which mother, as in this system I am following the

Buchans. One grandson is named as the father of two illegitimate children on separate

baptism records, and there is DNA evidence from descendants of each to support

this connection.

The children of person 5.2 are numbered 5.2.1, 5.2.2, 5.2.3

and so on. This approach signals that the siblings, having a one-digit index

number, are the first generation after George and Jean. The siblings’ children,

with two-digit index numbers, are the second generation after George and Jean.

My own grandchildren have eight-digit index numbers, so they are the eighth

generation from George and Jean. This gives everyone a unique number that instantly

identifies which sibling they descend from, and which generation from the

original couple they are. I often check the surrounding dates of birth of

anyone I add to the list, which is in generation order, to see that I am in the

ballpark of the correct generation.

Data points

The variables of most interest to me are about migration and

mortality. I therefore captured information in the following categories: Death

year, Age at death; County/state of death, Parish/town of death; Cause of

death, Burial parish/cemetery, Headstone, Informant, Relationship; Emigration:

y/n; Emigration country. The county/state of birth is the default for an

individual. Scotland is the default country, so that if born in another county,

this is entered as bEng or bUSA in the Emigration y/n. It is then possible to

indicate migration from a different base than in Scotland.

An interest in mortality is professional, being a now-retired

medical practitioner. I expect to see changing causes of death by age, gender

and over the centuries. The impact of early death of parents is more subtle. I

expect there to be impacts on family size, perhaps on family location,

remarriage, changing occupations and perhaps this might highlight a family for

closer attention. Another area of interest to me is occupational deaths, as my

ancestors Robert Buchan and his son Robert [who came to Australia] both died in

mining accidents. Sadly, I have found several similar deaths in their close

relatives. How many miners died of lung disease?

Some preliminary results

I started this process with the smaller families – those of William,

Andrew and Alexander. Isabella is a ‘mid-level’ sized family, large enough to

allow analysis.

The number of descendants of Isabella has increased from 289

(pre-May2025) to 434. The following table shows the availability of death data

for the Isabella branch. In Generation 2, I have not found records for two

children who died before 1855 when burial records are sparse. Increasingly, her

descendants are born outside of Scotland, ranging from 5% in Generation 3 to 73%

in Generation 7. This has reduced my capacity to obtain death certificates. Generations

8 and 9 are too recent to include any meaningful information, especially since

England and Wales index data is unavailable after 2000.

1= 3 records from England, 2=2 deaths in England

To date I have obtained 62 of 144 death certificates, with

nine more available to purchase online from either SP or GRO. The remaining certificates of deaths in

England, Wales and Northern Ireland after 1957, and in Australia, NZ, USA and

Canada are not obtainable. I will rely on certificates being published on

genealogy databases over time.

Although I have not yet decided how to code cause of death, in

general the specificity of this information increased over time. Infant deaths

declined, with infectious diseases decreasing such that congenital disease

becomes more common. Bronchopneumonia has been a constant cause of death,

across all ages. Three of her descendants died during the world wars on active

service. The last death due to tuberculosis occurred in 1930; while the first

recorded death due to cancer occurred in 1977.

The very much larger families of George (sibling 2) and

Robert (sibling 5), with 4-5 times more descendants than Isabella, will provide

much more information as most of these families stayed in Scotland. My own line

is an exception, with my x3 great-grandfather, Robert Buchan, being the very

first member of this entire family to emigrate outside Scotland, in 1852. Sadly

for my study, Andrew’s entire line is now outside Scotland. The patterns of

emigration will be another story altogether.

As progressively complete descriptions of the outcomes of my

Buchan family are available, I hope to publish the findings in this journal to

keep me focused and, I hope, to be of interest.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment